Nonwoven fabrics are engineered materials made by bonding or entangling fibers together into a sheet or web, without the need for weaving or knitting. In other words, nonwovens skip the yarn-spinning and fabric-weaving steps of traditional textiles – fibers (or polymer filaments) go directly from raw material to finished fabric. This report provides an overview of what nonwovens are, how they differ from conventional fabrics, and how they are made.

Overview of Nonwovens

Definition: A nonwoven is broadly defined as a sheet or web of fibers bonded together by mechanical, thermal, or chemical means, made directly from separate fibers or molten polymer, and not made by weaving or knitting.

Essentially, any fabric-like material that is formed without weaving yarns can be considered a nonwoven. Common examples include felt, disposable wipes, and the layers inside surgical masks. Nonwovens can be composed of natural fibers (like cotton, wood pulp, or hemp) or synthetic fibers (like polypropylene or polyester), or often a blend.

Key Properties: Nonwovens can be engineered with a wide range of properties to suit different applications. Depending on the fiber content and bonding method, a nonwoven material can be made to be highly absorbent or fully liquid-repellent, very soft and drapable or stiff, elastic or dimensionally stable, and so on. For example, a thin polyester nonwoven can be made water-repellent for use as a medical gown, while a cellulose-fiber nonwoven can be made highly absorbent for a wipe. Many nonwovens also have inherent porosity, since they are composed of tangled fibers with air gaps – this is great for filtration and breathability. Properties like flame retardancy, sterility (for medical use), insulation, and strength can be achieved by choosing appropriate fibers or treatments. This versatility is a key advantage of nonwovens – manufacturers can “dial in” specific properties by selecting different fiber types, web forming processed and bonding techniques to meet requirements.

Differences from Woven Textiles: Unlike traditional woven or knitted fabrics that gain strength from interlaced yarns, nonwovens derive strength from how fibers are bonded (by pressure, heat, or adhesives). Several characteristics distinguish nonwovens from woven cloth:

· Manufacturing Speed: Nonwoven production is often extremely fast and efficient, going from raw polymer or fiber to finished fabric in one continuous process. For instance, spunbond nonwoven lines can produce fabric at hundreds of meters per minute. Because of this, nonwovens are ideal for high-volume disposable products. The cost per unit can be much lower than a comparable woven textile.

· Cost & Economy: The high throughput of many nonwoven processes means they can be made very economically, especially for single-use items like wipes, medical gowns, diapers, and filters. Traditional fabrics require multiple steps (spinning yarn, weaving, etc.), which add time and cost.

· Customization: Nonwovens offer more flexibility in material selection – they can include natural fibers, synthetic fibers, or blends, and even incorporate recycled content. By changing fiber blends and bonding methods, manufacturers can achieve properties that might be difficult with woven cloth. For example, one can make a nonwoven highly porous for filtration or ultra-soft and lint-free for sensitive applications.

· Look & Feel: Nonwovens generally have a different appearance and feel compared to typical fabric. They may look like paper (e.g. some air-laid or wet-laid nonwovens) or felt (e.g. needle-punched nonwovens) or a thin web (like the layers of a surgical mask). Some nonwovens (like certain spunlace wipes) can be made to feel very cloth-like, but others might be stiffer or have a more uniform, plastic-like texture. In contrast, woven fabrics usually have a distinct thread pattern and a pliable drape.

· Performance Trade-offs: Woven fabrics tend to have higher tensile strength, while nonwovens often excel in properties like permeability and stretch. For instance, in geotextiles it’s noted that woven types have higher strength, whereas nonwoven types have higher flow rate (permittivity) and can elongate more under stress. Nonwovens are usually more porous and can handle fluid flow or filtration better than a tightly woven fabric, though they may not match the strength of a heavy woven unless specially reinforced.

How Nonwovens are Manufactured: There are several processes to make nonwoven materials, all involving two basic steps: (1) Forming a fiber web (laying fibers out into a loose batt or web), and (2) Bonding the web to add strength. Different processes use different methods for each step. Below is a brief overview of the major nonwoven manufacturing techniques:

· Spunbond & Meltblown (Spunlaid): In spunbonding, plastic pellets (usually polypropylene) are melted and extruded into continuous filaments, which are laid down onto a moving belt to form a web. The hot filaments bond to each other as they cool, and additional thermal bonding (through heated rollers; i.e. calendering) is often used to strengthen the web. This process is very fast and produces a fabric directly from polymer resin in one pass. Meltblown is a related process where the molten polymer is extruded into ultra-fine fibers using high-velocity hot air; these microfibers form a web with extremely small pore sizes (great for filtration). Spunbond fabrics are strong and used in things like agricultural covers and diaper coversheets, while meltblown webs are weaker but excellent as filter layers (often meltblown is layered between spunbond layers to make SMS (Spunbond-Meltblown-Spunbond) fabrics for medical masks, etc.). Bonding: by thermal self-bonding of fibers and calender (for spunbond), or self-bonding by fiber entanglement in the air stream (meltblown). (Economic note: high output, high initial machine cost, mostly synthetic polymers; Environmental note: uses plastic feedstock and a lot of energy for melting, but no water usage; products are recyclable if collected but typically not biodegradable.)*

· Spunlace (Hydroentanglement): Spunlace uses high-pressure fine water jets to entangle and bond a web of loose fibers. Typically, staple fibers (e.g. polyester, viscose, cotton, etc.) are first carded or air-laid into a fiber web, then multiple water jets punch through the web, tangling the fibers around each other. This mechanical entanglement produces a strong, flexible fabric without any binders or heat. Spunlace fabrics are known for being soft and cloth-like, with good drape and absorbency. They are widely used for products like wipes and cosmetic facial masks because of their textile-like feel. Bonding: by mechanical fiber entanglement with water (no added glue or melt). (Economic note: moderate speed, requires significant water and energy for water pressure and drying; good for medium-volume production; Environmental note: can use 100% natural or biodegradable fibers, and because no synthetic binder is needed, many spunlace products can be made compostable. However, the process uses large amounts of water which must be filtered and recycled, and energy for drying the web after entanglement.)

· Needle-Punch (Needlefelting): Needle-punched nonwovens are made by mechanically entangling fibers using thousands of barbed needles. A fiber batt (often of polyester, polypropylene, or natural fibers like wool or jute) is laid out (usually by carding or air-laying), then repeatedly punched by needles that drag and tangle fibers together. This creates a thick, felt-like fabric (often called needlefelt). The resulting material can range from fairly thin to very thick and dense, depending on needle density and layering. Bonding: purely mechanical, by fiber interlocking from needles. Needle-punched fabrics tend to be strong, with a fuzzy felt feel. Common uses include carpet underlays, automotive carpets and insulation, geotextile liners, and felt filters. (Economic note: relatively slower process and lower throughput than spunbond; equipment is simpler and can be run at smaller scale; Environmental note: can use a wide variety of fibers, including recycled fibers. In fact, a large portion of needle-punched felt worldwide is made from recycled polyester (e.g. from PET bottles), making it a very sustainable option. No water or chemicals are required in bonding, and products can be recyclable or even made from waste fibers.

· Airlaid: Airlaid nonwovens use airflow to disperse and deposit fibers (often wood pulp or other short fibers) onto a belt to form a web. This process is unique in that it can lay down fluff pulp fibers to form thick, highly absorbent sheets. Because pulp alone has little strength, airlaid webs are usually bonded with either latex binders (sprayed on and cured) or by incorporating thermoplastic binder fibers that are melted (thermal bonding). The result is a fabric that looks and feels somewhat like a thick paper towel. Bonding: usually chemical (latex adhesive) or thermal (melting binder fibers) or both. Airlaid fabrics excel in absorbency – for example, the absorbent core of many diapers and sanitary pads is an airlaid fluff pulp layer mixed with superabsorbent polymer. Other uses include disposable kitchen wipes, tabletop napkins, and medical pads. (Economic note: moderate production speed; the process is designed for making bulky absorbent cores in high volume; Environmental note: uses natural renewable fiber (pulp) as a main ingredient but often requires some synthetic binder fiber or glue. Newer airlaid products try to use biodegradable binders to improve end-of-life. The high pulp content makes airlaids more biodegradable than pure plastic nonwovens, but the added latex or plastic fibers mean the fabric isn’t 100% biodegradable unless special polymers are used.)*

· Thermally Bonded (Through-Air/Calendered): This category covers nonwovens made by first forming a web (usually via carding or air-laying) of thermoplastic fibers or bicomponent fibers and then bonding it by applying heat. In calender bonding, the fiber web is passed between heated rollers that partially melt and fuse the fibers at points (often one roller has an engraved pattern to create point bonds). This yields a thin, strong, but somewhat stiff nonwoven; it’s commonly used for hygiene product components (e.g. the top sheet of a diaper that has a soft perforated feel is a point-bonded polypropylene nonwoven). In through-air bonding, the fiber web (often containing bicomponent fiber that has a lower-melting sheath) is passed through an oven where hot air is blown through it, melting the binder fiber throughout the thickness to bond the web. Through-air bonding is used to make high-loft fluffy fabrics (like quilt batting or the cushion layer in diapers) that need bonding without crushing the loft. Bonding: by heat melting of fibers at either surface points or throughout the web. (Economic note: very high speeds are possible for thin calendared materials (used in disposable hygiene products); through-air is slower for thick items; Environmental note: no chemical binders needed, but the fibers must be plastic or have a plastic component to melt. These fabrics are not biodegradable (unless using bio-based plastic fibers), but they can be made with recycled polymers. Energy use is significant for heating.)*

· Chemically Bonded (Adhesive Bonded): In some nonwovens, an adhesive or binder is applied to the fiber web to glue the fibers together. This can be done by spraying, foaming or printing a latex (plastic) binder and then curing/drying it. It’s an older method and less common now for consumer fabrics because it adds chemicals and can make the fabric stiff. However, it is used in certain interfacing materials and some wipes or filter papers. For example, some cleaning wipes are made by bonding a blend of rayon and polyester with a latex resin – this gives a strong, paper-like cloth. Bonding: by chemical adhesive. (Economic note: equipment is relatively simple and low-cost; but the added binder increases material cost and requires a drying step; Environmental note: chemical binders can hinder recyclability and biodegradability. There is interest in developing bio-based and recyclable binders to improve this.)*

Figure 1: Multiple colored swatches of non-woven fabric. Nonwovens can be made in many colors and textures. Unlike woven textiles , nonwoven fabrics have a random fibrous structure and can resemble paper or felt.

Applications for Nonwovens

Nonwoven materials are found in an array of industries and products, often unseen but critical to performance. Because they can be engineered for properties like absorbency, filtration, softness, and strength at low cost, nonwovens have become the material of choice for many single-use goods and industrial products. Key sectors using nonwovens include insulation, hygiene products, medical supplies, automotive components, construction materials, and filtration systems. Below are some major industries and real-world applications:

Insulation

Insulation applications for nonwovens generally fall into a few categories, often overlapping in practice:

· Thermal Insulation: Reducing heat transfer is the primary goal. Many nonwoven insulations trap air within fibrous mats to slow conduction and convection of heat. Performance is measured by R-value (resistance to heat flow) – higher R-values indicate better thermal performance. Thick lofted nonwoven batts in walls or blankets around equipment help maintain comfortable indoor temperatures and improve energy efficiency.

· Acoustic Insulation: Nonwovens excel at absorbing and dampening sound. Needlepunch felts and high-loft mats are used as sound barriers in walls, ceilings, and automotive cabins to reduce noise transmission. By converting sound waves into low-grade heat within the fiber network, they improve acoustic comfort. For example, car headliners and engine bay liners use nonwoven insulation to absorb engine and road noise.

· Fire-Resistant Insulation: Certain nonwoven insulations are designed to resist flames and high heat. Mineral fiber batts (made of glass or stone wool) are naturally non-combustible and often serve as fire barriers in buildings. Likewise, specialty nonwovens from flame-resistant fibers (aramids, polyimides, etc.) are used in applications demanding fire protection. These materials help slow fire spread and can withstand extreme temperatures (some silica-based nonwoven blankets insulate up to ~1050 °C).

· Hybrid Solutions: Many insulation products now combine thermal, acoustic, and fire performance in one. Such hybrid nonwoven insulations deliver multi-functional protection – for instance, a mineral wool batt that provides heat retention, sound attenuation, and fire resistance. This enables meeting multiple building requirements with a single material. Hybrid insulation panels may also incorporate reflective foils or facings to enhance certain properties (e.g. adding a foil layer to reflect radiant heat while the fibrous layer absorbs sound).

Key Industries and Applications

Nonwoven insulation materials are employed in a wide range of industries and settings. Key applications include:

· Residential & Commercial Construction

In buildings, nonwovens are used extensively as thermal/acoustic insulation in walls, attics, roofs, and floors. Fibrous batts or rolls (often fiberglass-free polyester or mineral wool) are fitted between studs and joists to slow heat loss and also dampen sound transfer. Because of their fibrous nature, these materials can serve dual purposes, managing both heat and noise within indoor spaces. For example, polyester insulation panels made from recycled fibers are “hypoallergenic, do not collapse over time” and provide effective thermal and acoustic performance in walls.

Nonwoven insulators are also found in HVAC and piping applications. Flexible needle-punched blankets or wraps can be applied around ducts, boilers, or hot water tanks to retain heat and prevent condensation. Thanks to their breathability and moisture resistance, these nonwoven wraps conform to irregular shapes and maintain insulating performance even in humid conditions. Overall, in construction, nonwovens help buildings meet energy codes and comfort needs by insulating the building envelope (from foundations to rooftops) as well as mechanical systems.

· Automotive

Nonwovens are ubiquitous in automotive insulation for both thermal control and noise reduction. In a typical car, over 40 components incorporate nonwoven fabrics—from trunk liners and carpets to under-hood heat shields. These materials help dampen engine and road noise, line the cabin for a quieter ride, and insulate the interior from engine/exhaust heat. For instance, behind the dashboard and inside door panels, nonwoven pads absorb sound and vibration. Under the hood, a molded nonwoven hoodliner serves as a heat insulator and also a fire-retardant barrier over the engine. By building in these properties, automotive nonwovens enhance ride comfort while keeping vehicle weight low (they are much lighter than foam or rubber alternatives).

Notably, the rise of electric vehicles (EVs) has made acoustic insulation even more critical – without a loud engine, other noises (electronic whine, road, wind) become more apparent. Nonwoven sound insulation in the floor, wheel wells, and firewall helps counter this, creating a quiet EV cabin. Thermal insulation is also needed to keep the cabin warm since EVs lack waste engine heat. Manufacturers are using nonwoven materials to address these challenges, for example with battery compartment insulation. Lightweight fiber-based undershields and battery covers protect the battery pack, provide thermal management, and even add impact protection, all at about half the weight of traditional plastic components. In summary, nonwoven insulations in automobiles improve noise, heat, and safety performance in applications ranging from the engine bay to the interior cabin.

· Aerospace

In aviation and aerospace, lightweight high-performance insulation is paramount. Needled fiberglass or polyester nonwoven blankets are commonly installed in aircraft fuselage walls, ceilings, and floors to stabilize cabin temperature and absorb engine and airflow noise. These insulation blankets are often faced with a thin foil or film, which acts as a radiant heat barrier and fire blocker, meeting strict flame safety standards. High-performance fibers like aramid and silica are used in some aerospace nonwovens to withstand extreme temperatures – for example, silica-based felt insulation can remain effective up to about 1050 °C, providing fire protection in engine nacelles or around bleed air ducts.

Specialized nonwoven composites are also found in aircraft interiors: e.g. cushioned needlepunch pads serve as fire-blocking layers in seat cushions and carpet underlays, and acoustic fiber mats line bulkheads and flooring to deaden sound. The advantage of nonwovens is their ability to deliver required insulation performance at minimal weight, a critical factor for aircraft efficiency. Similar principles apply to spacecraft, satellites, and other aerospace vehicles, where advanced nonwoven insulations (often in multi-layer assemblies) protect sensitive equipment from extreme temperature swings and vacuum conditions. In essence, nonwovens enable aerospace engineers to meet thermal, acoustic, and fire requirements without the weight penalty of conventional insulation materials.

· Industrial & Specialized Uses

Beyond building and transport, nonwoven insulations are used in many industrial and specialty applications. One major area is high-temperature insulation for machinery and equipment. Needled felt mats made of heat-resistant fibers (such as fiberglass, ceramic, or basalt fibers) are used to wrap pipes, boilers, turbines, and furnaces, protecting workers and surrounding components from intense heat. These industrial insulation blankets can be custom-shaped, and because they contain non-organic fibers, they won’t burn or melt until extremely high temperatures (mineral fiber mats, for example, have melting points well above 1000 °C). This makes them vital for factories, power plants, and engines where thermal shielding and energy conservation are needed.

Nonwoven insulation also appears in protective gear and apparel. Firefighters’ turnout gear, heat-resistant gloves, and thermal liners for jackets often incorporate flame-retardant nonwoven layers. These textile layers provide critical insulation against extreme heat or cold while remaining flexible and lightweight. For instance, a meta-aramid nonwoven batting in a coat can protect a firefighter from ambient flames, and insulated nonwoven liners in outdoor gear (sleeping bags, parkas) help retain body heat in freezing conditions. In addition, appliances and electronics may utilize nonwoven insulation (e.g. an insulating felt around an oven or a water heater) to improve efficiency and safety. In all these specialized uses, the ability to tailor nonwoven material properties – fiber type, thickness, density, fire treatments – allows engineers to meet specific thermal or acoustic requirements that traditional rigid insulations might not satisfy.

Material Choices

A variety of fiber materials are used to manufacture nonwoven insulation, each offering distinct benefits. Key categories include:

· Synthetic Fibers: Polyester (PET) and polypropylene are widely used in insulation felts and batts. They are lightweight, resistant to moisture and mold, and can be made from recycled plastics. For example, many polyester insulation batts are made from recycled PET bottles and are themselves recyclable after use. Synthetic fiber insulations are also non-irritating to handle (unlike glass fibers) and can be engineered with specific fiber sizes to tune their loft and insulating value.

· Natural Fibers: Renewable fibers like wool and cotton can be formed into nonwoven insulation mats as eco-friendly alternatives. Wool in particular has excellent moisture-regulating ability – it can absorb up to about 30% of its weight in moisture without feeling wet, which helps prevent condensation and mold. Wool or cotton batts provide decent thermal insulation and sound absorption while being biodegradable and low-emission (no formaldehyde binders). Their fire resistance varies; wool is naturally self-extinguishing to a degree, whereas cotton typically requires treatment for fire safety.

· Bio-Based (Plant) Fibers: Recently there is growing interest in insulations made from plant-derived fibers such as hemp, flax, or jute. Hemp fiber nonwovens, for instance, have been introduced as a sustainable, non-toxic insulation replacement for fiberglass. These batts (often 85–90% hemp fiber with polyester

binder) offer comparable R-values and have the advantage of being carbon-sequestering and compostable. Hemp insulation is also noted for its ability to “absorb, store, and release heat” and buffer moisture, which can stabilize indoor humidity and reduce energy use. The use of agricultural fibers in insulation is an emerging trend to reduce the environmental footprint of buildings.

· Mineral Fibers: Mineral wool insulations, including fiberglass (glass wool) and stone wool, are classic examples of nonwoven insulators. They consist of molten glass or rock spun into fibrous mats, often held together with a resin binder. These materials are naturally fireproof – glass and stone fibers will not burn and can withstand temperatures over 1000 °C before melting. Mineral fiber batts are widely used in construction for thermal and acoustic insulation, and their inorganic fibers do not support mold growth or pests. However, loose fiberglass can irritate skin and lungs, so encapsulated or faced forms (sometimes using a nonwoven fabric facer) are preferred for handling. Newer formulations avoid formaldehyde binders to improve indoor air quality.

In practice, many insulation products blend fiber types or use special additives (for example, bonding polyester and natural fibers, or adding aerogel particles to a nonwoven mat) to achieve the desired balance of insulation value, strength, flame resistance, and sustainability.

Performance Factors

When evaluating nonwoven insulation materials, a number of performance factors come into play:

· R-Value (Thermal Resistance): Insulation effectiveness is often quantified by its R-value per inch of thickness. Nonwoven insulations can provide high R-values by trapping air within fine fiber networks. For instance, polyester and fiberglass batts typically deliver R-values around 3–4 per inch, helping keep buildings warm in winter and cool in summer. Sufficient thickness or multiple layers may be needed to reach the target R-value for a given climate or application.

· Breathability & Moisture Management: A good insulation not only blocks heat flow but also manages moisture. Many nonwoven fabrics are vapor-permeable – they allow moisture vapor to pass through rather than trap it. This prevents condensation inside walls or equipment. For example, certain polypropylene nonwoven facings and housewraps are designed to let buildings “breathe,” letting water vapor escape and thus avoiding mold. Hydrophobic fibers (polypropylene, polyester) won’t soak up water, while natural fibers like wool can safely hold some moisture and release it when conditions dry. The breathability of an insulation assembly is critical for durability in building envelopes and for comfort in apparel.

· Durability & Stability: Nonwoven insulations are valued for their long-term stability – quality batts or felts will retain thickness and performance over time. Unlike loose fill that can settle, a bonded fiber mat remains in place and resists collapsing. Recycled PET insulation, for instance, has been noted to “not collapse over time,” maintaining its loft and insulating air pockets. Durability also means resisting vibration or compression in use (important in vehicles) and withstanding temperature cycles without degrading. Many nonwovens are engineered to avoid fiber degradation or binder deterioration, ensuring the insulation continues performing for the life of the product.

· Mold and Mildew Resistance: Because insulation often operates in enclosed or damp-prone spaces, resistance to biological growth is key. Synthetic and mineral fiber insulations are inherently mold-resistant – they contain no food source for fungi and typically do not absorb and hold liquid water. Tests show polyester batts are highly resistant to moisture, mold, and mildew. By allowing moisture to dissipate, nonwovens minimize the risk of mold growth that could degrade insulation and indoor air quality. (In contrast, some conventional insulations like paper-faced products or certain foams can trap moisture or foster mold if not properly installed. Nonwovens can be designed to avoid these issues.)

· Fire Performance: For many applications, an insulation’s behavior in a fire (flammability, smoke production) is a crucial performance factor. Materials like fiberglass, mineral wool, and specially treated fabrics achieve Class A fire ratings (noncombustible or minimal flame spread), making them suitable for fire-resistant construction. Where needed, insulation can double as a fire barrier – e.g. nonwoven fire-blocking layers in transportation or building assemblies that must meet fire codes. The ability to withstand heat for a period (measured by standards like ASTM E119 or similar) can be a deciding factor in material choice. Nonwovens offer options from inherently fireproof fibers to chemically treated flame retardant grades to meet these safety requirements.

·Recyclability & Sustainability: Increasingly, the end-of-life and environmental profile of insulation are considered performance factors as well. Many nonwoven insulation materials are designed to be recyclable or made from recycled content, reducing landfill waste. For example, a pure polyester insulation can be shredded and reprocessed into new fiber products. Sustainability certifications now look at whether insulation has low VOC emissions, contains renewable or recycled materials, and can be disposed of safely. These considerations, while not affecting the immediate thermal or acoustic performance, are important in product selection and are discussed further in the next section.

Hygiene and Personal Care: The hygiene industry is one of the largest users of nonwovens. Disposable diapers are a prime example – they use multiple layers of nonwoven fabric (a soft top sheet, an absorbent airlaid or tissue core, and a waterproof spunbond or film backsheet). Other examples are baby wipes and facial wipes (usually spunlace nonwovens for softness), feminine hygiene products and adult incontinence pads (which use nonwoven covers and absorbent cores), and disposable towels. The reasons are clear: nonwovens provide the necessary absorbency, softness, and cost-effectiveness for single-use items. For instance, the top sheet of a diaper that touches the skin is often a hydrophilic thermally-bonded nonwoven, designed to quickly pass liquid but stay relatively dry to the touch.

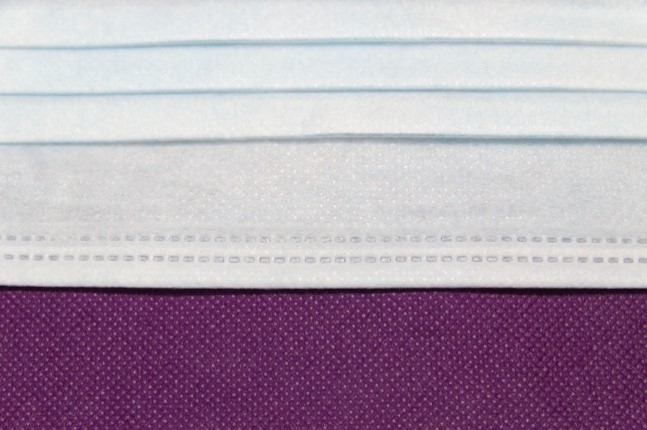

Medical and Healthcare: Many medical disposables are made from nonwovens because of their sterility, barrier properties, and low cost. Examples include surgical face masks (typically a multi-layer nonwoven structure: an inner and outer spunbond layer for strength and fluid resistance, with a meltblown microfibrous layer in between for filtration), surgical gowns and isolation gowns (spunbond or SMS nonwovens that are lightweight and liquid-repellent), caps and shoe covers, and sterilization wrap for surgical instrument trays (often a spunbond-meltblown laminate). Wound care products also use nonwovens – e.g. absorbent pads and bandage backing layers. In healthcare settings, one-time use and cleanliness are paramount, and nonwovens meet these needs by being produced sterile and in large volumes. A dramatic example was the COVID-19 pandemic, where the demand for meltblown nonwovens (for N95 mask filters) skyrocketed due to their critical role as filtration media.

Automotive and Transportation: Cars and other vehicles rely on various nonwoven fabrics for performance and comfort. A car’s interior, for instance, uses needle-punched nonwoven felts for carpeting and insulation (including trunk liners, hood liners, and sound-damping pads). These felts are durable, moldable, and often made from recycled fibers (e.g. many car carpets are made from recycled PET bottle fibers via needlepunching). Nonwovens are also used in vehicle cabin air filters (usually a pleated wet-laid or meltblown material to trap dust), in fuel and oil filters, and even as backing for interior trim and headliners. In addition, high-end battery separators in electric vehicles can be specialty nonwoven membranes. The automotive industry values nonwovens for their combination of light weight, moldability (for felts), and acoustic insulation properties.

Construction and Geotextiles: The construction sector uses very heavy-duty nonwovens, especially in geotechnical applications. Geotextiles are large sheets of nonwoven (or sometimes woven) fabric used underground or in infrastructure projects – for example, a polypropylene needle-punched geotextile might line a roadbed to stabilize soil and provide drainage. Nonwoven geotextile fabrics allow water to pass through (preventing water pressure buildup) while filtering soil, and they add a layer of reinforcement. They are also used in erosion control blankets and roofing underlayment. Roofing materials often include a spunbond polyester mat as the carrier for asphalt shingles, or a durable polypropylene nonwoven layer as a roofing underlayment (the sheet applied under shingles or tiles) because it is tear-resistant and waterproof. House wrap (like the material Tyvek®) is a flash-spun (a fiber production process where a polymer solution is rapidly heated and ejected through a nozzle into a lower-pressure chamber, causing the solvent to flash evaporate. This results in ultrafine, continuous fibers that form a nonwoven fabric with high strength and barrier properties.) polyethylene nonwoven that acts as a breathable water barrier on building exteriors. Additionally, in flooring and carpets, nonwovens serve as the primary backing or as carpet padding.

Filtration: Filtration is a natural fit for nonwovens due to their porous structure. Nonwoven filter media appear in air filters (HVAC filters, HEPA filters, vacuum cleaner bags) and liquid filters (water filters, industrial fluid filters, coffee and tea bags). For example, HEPA filters are often made from microfiber meltblown polypropylene nonwovens that can trap very fine particles. Engine air intake filters use thick pleated nonwovens (sometimes wet-laid fiberglass mats or polyester). In water purification, nonwoven depth filters made of meltblown fibers can remove sediment. The advantage of nonwovens in filtration is the ability to create a random fiber matrix with controllable pore sizes and even add electrostatic charge (as in N95 mask media) for improved particle capture. Nonwovens also avoid the fraying of woven fibers, which is important for consistent filter performance.

Other Applications: Beyond the major sectors above, nonwovens find use in many everyday and specialty products. For instance, in home furnishings, nonwoven interlinings are used inside furniture and mattresses, and quilted nonwovens serve as mattress pads or comforter insulation. In apparel, nonwovens serve as interfacing (the stiffer fabric pieces inside collars, cuffs, etc., often made of a point-bonded nonwoven) and as liners or protective clothing (e.g. disposable coveralls). In the consumer realm, reusable shopping bags made of spunbond polypropylene have become popular as a fabric-like but inexpensive bag (those typically colored tote bags that feel a bit like fabric are actually nonwovens). Even items like tea bags and vacuum cleaner dust bags are made from special nonwoven paper-like fabrics. The breadth of applications continues to grow as new nonwoven technologies emerge.

Figure 2: Close-up of two common nonwoven products. Top: Layers of a disposable surgical mask (made of thin spunbond and meltblown nonwovens). Bottom: Purple reusable shopping bag made of spunbond polypropylene nonwoven. These everyday items showcase how nonwovens provide both filtration and fabric-like durability in various contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Nonwoven Processes

The nonwoven manufacturing process chosen for a product can significantly impact its cost, performance, and environmental footprint. In this section, we compare the major nonwoven processes with regard to sustainability (materials and energy usage) and economics (production cost and scalability). Each technique has its strengths and weaknesses:

Sustainability Considerations

From a sustainability perspective, key factors include the raw materials used (are they renewable or recycled?), the energy and resources required in production, and end-of-life options (recyclability or biodegradability).

Traditionally, many nonwovens have been made from synthetic plastics like polypropylene or polyester derived from petroleum. These offer low cost and excellent performance, but they are not biodegradable, contributing to plastic waste if not recycled. There is a major push in the industry to improve sustainability by shifting to bio-based or recycled inputs and designing products for better end-of-life outcomes. For example, some manufacturers now use 100% recycled polyester fibers to produce needle-punched felts for automotive and furniture use, effectively turning post-consumer plastic bottles into new textiles. This not only diverts waste from landfills but also reduces the need for virgin polymer.

Another approach is using natural fibers (like cotton, viscose, or hemp) in place of synthetics. Spunlace nonwovens, for instance, can be made from 100% cellulosic fiber blends and still achieve high performance, resulting in a fabric that is biodegradable and even compostable. Fibers like hemp are gaining interest as well – hemp is a fast-growing renewable crop that requires less water and chemicals than cotton, and it can produce strong, absorbent fibers that work in nonwovens. Incorporating such fibers can improve the overall sustainability profile of the product (reducing fossil plastic content and enabling biodegradability).

Energy usage is also crucial. Processes like spunbond and meltblown, which involve melting polymers, are energy-intensive but very efficient per unit of output (because they produce large volumes quickly). Spunlace uses electrical energy for water pressure and then thermal energy to dry the web – water recycling systems are needed to make it environmentally sound. Needle-punching is relatively low-energy (mainly running motors for the needles) and doesn’t require water or heat in the bonding step, which is a sustainability advantage. Chemical bonding processes have to manage the environmental impact of adhesive chemicals (VOC emissions during drying, and the fact that the resulting fabric has synthetic resin added).

End-of-life is a challenge for many nonwovens used in disposables (like wipes and diapers) – they often end up in landfill or incineration. To address this, companies are innovating with biodegradable nonwovens (for example, using PLA bioplastic or cellulosic fibers that can break down), and with recycling programs (collecting used nonwoven products for material recovery). However, recycling nonwovens can be difficult if they are contaminated (as with medical or hygiene waste) or if they are composites of different materials. Thus, material choices at the design stage are important: using a single polymer type or all-natural components can improve recyclability or compostability. Industry trends show many suppliers publishing sustainability reports and aiming to cut energy use and carbon emissions per kilogram of fabric produced.

Cost and Economic Factors

When comparing manufacturing techniques, cost is influenced by equipment investment, throughput (how many kg or square meters per hour can be made), labor, and materials. Processes like spunbond/meltblown have very high upfront machinery costs, but they yield huge volumes of product at low unit cost. This makes them economically unbeatable for large-scale products like diaper components or medical gowns – once running, a spunbond line produces fabric so rapidly that the cost per square meter is very low. The trade-off is that it’s only cost-effective at scale; smaller production runs wouldn’t justify the investment.

Spunlace (hydroentanglement) has a moderately high capital cost and slower throughput than spunbond, partly due to the bottleneck of drying the product. As a result, spunlace fabrics (like wipes) generally cost a bit more per unit area than spunbond fabrics. However, spunlace allows use of inexpensive raw materials such as viscose pulp or short fibers, and it doesn’t require expensive bicomponent fibers or specialty polymers. Economically, spunlace is chosen for products where the soft feel or natural fiber content justifies a slightly higher material cost (e.g. premium personal care wipes).

Needle-punch lines are comparatively lower in cost to set up and can be scaled from small to large fairly easily. They run slower, but they can make very heavy weight fabrics in one pass (something spunbond can’t easily do). The cost per kg can be low especially if using cheap or recycled fiber feedstock. For instance, using recycled PET for automotive felt not only is eco-friendly but also cost-effective because the raw material (bottle flakes) is cheap. Needle-punched products are often in durable applications, where the cost is justified by the long service life (e.g. geotextile in a road will last years).

Airlaid and chemical-bonded processes often use inexpensive raw fibers (fluff pulp or waste cotton, etc.) but require binders or specialty fibers. The added cost of latex binders and the drying step means chemical-bonded nonwovens can be a bit more costly per unit than purely thermally bonded ones. However, because airlaid is ideal for making absorbent cores, its economic value is judged by functionality – a diaper core made by airlaid might reduce the quantity of expensive absorbent polymer needed, balancing the cost.

In summary, processes with the highest throughput (spunbond, meltblown, thermal calendering) are chosen for high-volume, low-cost goods (even if the machinery is expensive, the volume amortizes it). Processes that offer special properties (spunlace for softness or ability to use natural fibers, needle-punch for thickness and durability, airlaid for absorbency) are chosen when those properties add value to the end product, even if the unit cost is a bit higher. Manufacturers must weigh raw material costs too: synthetic polymer pellets (for spunbond) might be cheaper per kg than high-quality cotton or rayon fiber (for spunlace), so the material choice influences cost as much as the process.

Process Strengths and Weaknesses (Economic & Environmental)

To consolidate the comparison, the table below summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of each major nonwoven process, considering both economic and environmental factors:

Figure 3: This table provides a comparative analysis of major nonwoven manufacturing processes, highlighting their economic and environmental strengths and weaknesses. It outlines key considerations such as material efficiency, sustainability, production speed, cost implications, and recyclability. By understanding these trade-offs, manufacturers can select the most suitable nonwoven process for their applications, balancing performance, cost-effectiveness, and environmental impact.

Overall, each nonwoven process strikes a balance between cost, performance, and environmental impact. High-speed processes (like spunbond) offer cost savings and uniform quality but rely heavily on synthetic inputs, whereas processes like needle-punch or spunlace provide more routes to use recycled or natural fibers albeit at higher cost. The nonwovens industry is actively evolving to address sustainability concerns – for example, developing bio-based polymers for spunbond, improving energy efficiency in processes, and innovating recycling methods for used nonwovens. By understanding the trade-offs of each process, companies can choose the appropriate nonwoven technology that meets their product requirements and aligns with their economic and environmental goals.

In conclusion, nonwovens have become indispensable in modern life, from the diapers and wipes we use daily to the filters cleaning our air and the materials reinforcing our roads. Nonwoven technology offers incredible flexibility to tailor material properties, and with growing emphasis on sustainability, it continues to innovate. By selecting the right process and materials – whether it’s a fast, efficient spunbond for a disposable medical gown, or a recycled fiber needle-punched felt for a car interior – manufacturers can leverage nonwovens to create products that are effective, cost-efficient, and increasingly eco-conscious. The future of nonwovens will likely see even more integration of renewable resources, cleaner production energy, and circular lifecycle designs, truly making it an advanced textile solution for the 21st century.

#Nonwovens #Insulation #ThermalInsulation #Acousticinsulation #BuildingMaterials #BioBased #Spunbound #Spunlace #Airlaid #Thermalbonded #Chemicalbonded #Hygiene #Automotive #GreenBuilding #NonWovenTechnology www.indhemp.com

IG: @indhemp

Citations for Nonwovens 101 White Paper

1. INDA & EDANA. (2024). Global Nonwoven Markets Report 2024. INDA – Association of the Nonwoven Fabrics Industry. 2. Nonwovens Industry. (2023). What Are The Types Of Nonwovens? Retrieved from www.nonwovens-industry.com.

3. EDANA. (2024). Nonwoven Manufacturing Processes: An Overview. European Disposables and Nonwovens Association.

4. Berry Global. (2023). Innovations in Spunbond and Meltblown Nonwovens for Filtration and Hygiene. Berry Global Technical Report.

5. Freudenberg Performance Materials. (2024). Recycled PET in Nonwoven Automotive Applications: Sustainable Solutions. Freudenberg Sustainability Report.

6. Ahlstrom-Munksjö. (2024). Biodegradable Nonwovens for Medical and Hygiene Applications. Ahlstrom Technical White Paper.

7. Suominen Corporation. (2024). Hemp-Based Spunlace Nonwovens: A Sustainable Alternative to Synthetic Wipes. Suominen Research and Development Report.

8. Hempitecture. (2023). Hemp Fiber in Construction Nonwovens: Insulation and Acoustics. Retrieved from www.hempitecture.com.

9. Automotive Nonwovens Market Report. (2023). Applications of Needlepunched Nonwovens in Vehicle Interiors and Acoustic Insulation.

10. Geotextile Applications Review. (2024). Performance Characteristics of Nonwoven Geotextiles for Erosion Control and Drainage.

11. Filtration Media Research Institute. (2023). Efficiency and Performance of Meltblown Nonwoven Filter Media.

12. Sustainable Nonwovens. (2024). The Role of Natural Fibers in Reducing Plastic Use in Nonwoven Products.